The year now coming to an end has been good for education reformers. That doesn't mean it has been a good for education, necessarly; but reformers have had a field day, blaming teachers and teachers' unions for almost every problem in the schools.

In 2011 we were warned that America's educational decline undermined our standing in a global economy. We heard that charter schools and vouchers would save U. S. education. Arne Duncan, U. S. Secretary of Education, pushed the idea that standardized testing was the key. Michelle Rhee, the Queen of Hearts in reforming circles, insisted that all school improvement boiled down to better teachers in the classrooms. Steven Brill--a lawyer, by trade--wrote a book, laying out the same essential case. And Davis Guggenheim's savaged teachers as lazy, incompetent union bums in the movie Waiting for Superman.

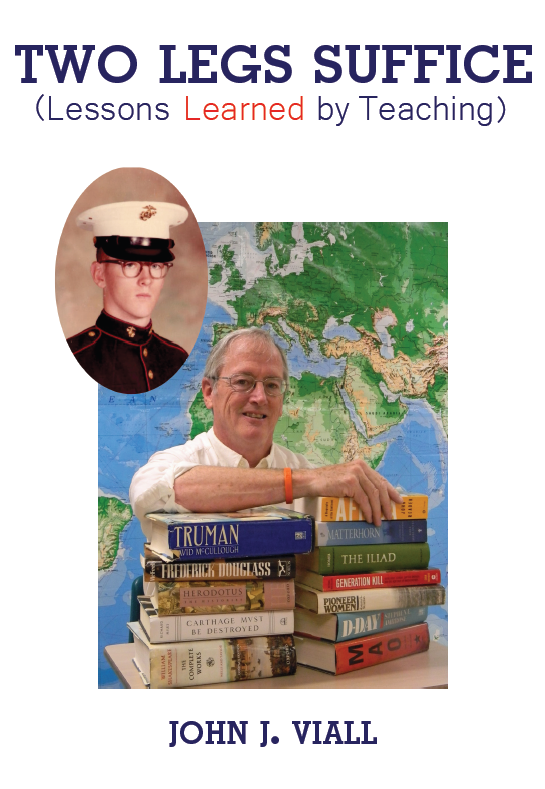

Meanwhile, I continued to amuse myself, trying to write a book about teaching. Naturally, I am making myself the handsome hero of the story. When Hollywood buys the rights, I even know who I want to play me in the film version: Brad Pitt.

(I think we look like twins.)

At any rate, here are some education statistics you might have missed recently:

0: We know U. S. schools are killing our nation's standing in the global economy, right? This number represents the growth in the Japanese economy since 1991 (it was $5.7 trillion two decades ago and it's $5.7 trillion now), despite a "superior" education system. In a survey done in 2009, comparing fifteen-year olds from 65 countries, Japanese students ranked #5 in reading, #4 in math, and #2 in science.

1: Number of unions representing teachers in the Wyoming City Public Schools, here in Ohio, where graduation rates are 98% and 2% of children qualify for the federal free lunch program. Same number representing teachers in Cincinnati Public Schools (bordering the Wyoming schools) where graduation rates are 81.9% and roughtly 60% of students qualify for the same program.

1.8: Estimated % growth of U. S. economy in 2011; critics say it's the public schools' fault. (U. S. public school teachers are apparently a bunch of miscreants.)

4.4: In 2009, Finland ranked #2 in that same survey of fifteen-year olds in reading, #2 in math and #1 in science. Finland is also a socialist country and only 4.4% of children grow up in poverty. In the United States, the comparable figure is 22%.

5:42: Hours and minutes spent daily watching TV or playing video games, average child in the U. S., age 8-18, compared to 38 minutes with printed material. (See: U. S. test scores below.)

6: Number of years actually spent in the classroom by leading voices in education reform, including Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg of New York, Joel I. Klein and Catherine Black, two recent chancellors of the New York City schools, Bill Gates and Melinda Gates and Eli Broad, billionaire philanthropists, Jon Schnur, who runs the school-reform group New Leaders for New Schools, Brill, Rhee, who promised to save the Washington, D. C. schools, Guggenheim, Chester Flynn Jr., think tank expert and staunch advocate of No Child Left Behind, Duncan, and six other U. S. secretaries of education, combined. That's right: combined.

8: Percentage growth of Brazilian economy in 2010. Brazil ranks 52nd in reading, 57th in math and 53rd in science out of 65 nations.

10: Percentage of babies born in Scioto County, Ohio, with illegal drugs in their blood. (You can see where this might be hard to pin on teachers.)

12: U. S. ranking in survey of 65 nations in reading (three-way tie with Iceland and Poland).

14+: Hours the average student in South Korea spends per day in school, doing homework, and in special after-hours tutoring sessions. In 2009, South Korea ranked #1 in the international survey noted above in reading, #1 in math and #3 in science.

15: One out of every fifteen U. S. high school students admits smoking marijuana on a nearly daily basis in 2011.

17: U. S. ranking in science knowledge, for fifteen-year-olds, out of 65 nations.

25: U. S. ranking in math, above.

33: U. S. standing, out of 33 "advanced economies," in a survey by the International Monetary Fund, in a ranking of preterm births and infant mortality.

36: Dollars per month, average pay for garment workers in Bangladesh, where exports have doubled since 2004. (You figure a superior system of education has nothing to do with this trend.)

43: Number of points higher--average SAT math scores--of Asian American students, who attend the same "failing schools" as white, black and Hispanic students.

46: Percentage of American adults who admit they did not read a single book last year not required for school or work. (See U. S. reading scores above.)

96: Number of reporters who showed up in 2009, to watch Tom Brady's first practice after missing most of the preceding NFL season with a serious knee injury. (You couldn't get 96 reporters to show up to watch the best teacher in America work in the next 96 years. We don't exactly focus on education in this country. See Japan and South Korea, above.)

108: Number of major league baseball players taking prescribed medications for A.D.D. and A.D.H.D. in 2008, after Major League Baseball began testing for amphetamines. (It makes you wonder if doctors might not be over-doing.) More generally, the Mayo Clinic estimates that 7.5% of all U. S. students are now taking Ritalin for A.D.D. and A.D.H.D.

200: Estimated murders of children in the U. S. by their parents every year. (Not all parents are the same and it's hard to see how vouchers will solve every "school" problem.)

240: Days spent per year in school by the average Japanese student. If U. S. students score lower than the Japanese it may be due in part to the fact that the Japanese boy or girl attends as many days in 3 years as his or her American peer does in 4.

245: Chicago public school students killed or wounded, mostly as a result of gang violence, during the 2009-2010 school year, almost entirely outside of schools and off school grounds. (This is the district Arne Duncan "fixed," by the way.)

670: Length in pages of the No Child Left Behind Law, designed to close the achievement gap between races, (see Asian American students, above) and passed by Congress in 2002, requiring schools to insure that every child is proficient in reading and math by 2014. This gap is entirely the fault of schools, even though black males are six times more likely to be murdered than white males, blacks have an unemployment rate twice as high as whites, a life-expectancy four years shorter, and are three times more likely to raise their children in single-parent homes.

8,500: child abuse and neglect cases in one year in Hamilton County, Ohio. Call Children's Services in your area for comparable statistics. (See: vouchers and charter schools, above.)

17,000: School resource officers presently employed in U. S. schools (a euphemism for "police" in halls).

132,000: Students now in U. S. public schools, classified as "severely disabled" . (See: No Child Left Behind, above.) This represents only a small fraction of the 6.5 million students on special education plans in the public schools.

954,914: Homeless children in America, according to most recent statistics by the U. S. Department of Education. (Charter schools? Really? That's your answer?)

1,500,000: U. S. students, grades K-12, with at least one parent behind bars at any given moment.

5,000,000: yearly salary of Ronald J. Packard, chief executive of K12 Inc., the biggest for-profit company in on-line education. Packard's schools are almost entirely funded by taxpayer money, based on number of students enrolled.

26,500,000: Money spent by K12 Inc. in 2010 on advertising; i. e. spending taxpayer money to convince students to sign up for internet classes, funded by taxpayer money. (Repeat cycle until taxpayers get too dizzy.)

31,650,000: Value in dollars, added incentives not included, of 8-year contract signed by John Calipari in 2009 to coach the University of Kentucky men's basketball team. Ironically, schools where Calipari coached previously were twice forced to forfeit games due to NCAA rules violations. Memphis forfeited its entire 2007-08 season (38 wins) after investigators discovered that at least one star player, reportedly guard Derrick Rose, and probably two, had other students take the SAT tests for them.

Could it be that we have a social problem in this country, not really a school problem?

As I. F. Stone once noted, "There are countries in which the ignorant have respect for learning. This is not one of them."

Friday, December 30, 2011

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

America's Teachers Stink Up the Place Again!

I'm a former teacher. So it's hard to have to face up to the facts about how bad America's teachers really are. In fact, it can be downright depressing. Time for a glass of spiked eggnog, I suppose.

Even the liberal New York Times piled on recently, in a story titled "Death Knell for the Lecture: Technology as a Passport to Personalized Education."

The focus of the story was actually the promise of internet teaching--but to make internet teaching sound like the solution you had to first identify the problem. In the first paragraph, then, we learned that among developed countries the United States ranked 55th in quality of elementary math and science education, 20th in high school completion rate and 27th in the fraction of college students receiving undergraduate degrees in science or engineering.

Bad schools and bad teaching, obviously.

The point was simple: We needed to replace bad teachers with superior internet lessons. Or we needed to replace bad teachers with cardboard cutouts or mannequins or maybe lamp posts. Whatever. We're 55th among developed nations!

It makes you wonder, though. What do these kinds of lists actually prove? I decided to do a little sleuthing.

Clearly: worst cops in the world.

We learn that America has absolutely the worst dieticians in the civilized world. Online dieting advice probably represents the last hope for fat people in the District of Columbia and all the fifty states.

Thank god, though, for America's judges! Clearly the best in the world. Where do you think we stand in rates of incarceration? Not 20th, for god sakes, not 27th. Certainly not 55th. No! We're #1. Liechtenstein has the worst judges, with only 19 people per 100,000 behind bars (you figure their cops must be too inept to catch anyone). Japan (58) and South Korea (94) beat us in education but their judges are pathetic, and probably need a few internet lessons on how to run an effective justice system. China? Failing badly. Only 122 prisoners. Mexico? No good. Only 200. Puerto Rico finishes in 35th place (303 prisoners) out of 212 nations; but they're just copying us. Grenada is #13 with 423, The Seychelles # 6 with 507, and Rwanda is #2 with 595.

Thank god we live in the United States of America, with the best jurists in the world--maybe in the universe! We lock up 743 people for every 100,000 in population.

That's what simple lists prove--and when I get the first Pulitzer prize ever awarded to a blogger, you can say, "I knew him before he became a famous celebrity and his head got all swelled."

And the first time I meet Lindsay Lohan at some big Hollywood party, you know what I'm going to say? "Baby, you need to think seriously about emigrating. Yeah. Liechtenstein would be cool."

For even more chilling statistics please go to: "Numbers Don't Lie: Our Teachers (and Doctors) Are Failing."

If you're a teacher (or a teacher's friend) consider spreading the word about this blog, or becoming a "follower" (not in any cult-like sense).

I intend to speak for all good teachers whenever I can.

Even the liberal New York Times piled on recently, in a story titled "Death Knell for the Lecture: Technology as a Passport to Personalized Education."

The focus of the story was actually the promise of internet teaching--but to make internet teaching sound like the solution you had to first identify the problem. In the first paragraph, then, we learned that among developed countries the United States ranked 55th in quality of elementary math and science education, 20th in high school completion rate and 27th in the fraction of college students receiving undergraduate degrees in science or engineering.

Bad schools and bad teaching, obviously.

The point was simple: We needed to replace bad teachers with superior internet lessons. Or we needed to replace bad teachers with cardboard cutouts or mannequins or maybe lamp posts. Whatever. We're 55th among developed nations!

It makes you wonder, though. What do these kinds of lists actually prove? I decided to do a little sleuthing.

If we use the same simple approach, we uncover a variety of chilling problems that demand immediate internet action. Online cops, anybody? In a recent survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development the United States finished dead last (cheap pun absolutely intended), 32nd out of thirty-two advanced nations, when it came to murder rates. And we're dead last by six feet and a mile. The Netherlands fell to tenth with one murder per 100,000 population. Finland finished one step above us, in 31st, with 2.5 murders. The United States landed in the morgue with 5.2 murders per 100,000 population.

Clearly: worst cops in the world.

According to another chilling survey we ranked 30th out of thirty advanced nations in obesity rates. So what do we learn from studying this chart?

We learn that America has absolutely the worst dieticians in the civilized world. Online dieting advice probably represents the last hope for fat people in the District of Columbia and all the fifty states.

|

| Maybe we should jail more teachers? |

Thank god we live in the United States of America, with the best jurists in the world--maybe in the universe! We lock up 743 people for every 100,000 in population.

That's what simple lists prove--and when I get the first Pulitzer prize ever awarded to a blogger, you can say, "I knew him before he became a famous celebrity and his head got all swelled."

And the first time I meet Lindsay Lohan at some big Hollywood party, you know what I'm going to say? "Baby, you need to think seriously about emigrating. Yeah. Liechtenstein would be cool."

For even more chilling statistics please go to: "Numbers Don't Lie: Our Teachers (and Doctors) Are Failing."

If you're a teacher (or a teacher's friend) consider spreading the word about this blog, or becoming a "follower" (not in any cult-like sense).

I intend to speak for all good teachers whenever I can.

Monday, December 26, 2011

Old Tools, New Tools in the Classroom: The Battle is Unchanged

I've been reading--once again--about how computers are going to save U. S. education. And I admit: I'm not really sold. Maybe it's because I use Facebook regularly. Don't get me wrong. I like Facebook. Still, it reminds me of something Henry David Thoreau said when the world was "speeding up" in the 1840s, with the new telegraph, and the new railroads cutting deep into his beloved woods.

"Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys," he grumbled, "which distract our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end...We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate."

That probably sums up every status update I've posted for the last six months.

I remember when my old school district started bringing computers into classrooms and setting up computer labs and hearing that technology was going to revolutionize education. I remember learning how to use Power Point and how to upload pictures from the Internet for use in lesson plans.

It was going to be great!

Now, instead of the tired old way, writing "AMERICAN CIVIL WAR (1861 to 1865)" on the blackboard with a piece of chalk, we could put it into Power Point. Then the letters would come flying out of a corner of the computer screen and spell out:

Of course, computers opened up a vast ocean of knowledge to students. Some dived in; and others merely dipped their toes. Others, still, walked the beach checking out the hot young guys and the tanned girls in their bikinis.

In fact, if you took a class to the computer lab and put everyone to work some students buckled down, and got excited about what they could find. Others surfed the web when you weren't looking or played electronic Solitaire. You could find interesting primary sources on the web; or you could go to Wikipedia, do a bit of quick cutting and pasting, and turn in the mishmash as "original" work and hope your teacher went away. You could even find sites pedaling pre-written term papers on all kinds of subjects for the right price. Or you could go to YouTube and find helpful tips on how to cheat on tests.

One suggestion: A) tear off old label from a Desani water bottle; B) scan label on computer; C) write tiny cheat sheet notes on back of new label: D) glue fake label back on bottle; E) carry bottle to next test. Drink as needed and refresh.

Improved means to an unimproved end.

I don't mean to sound like a Luddite here; I know computers can help good teachers in the classroom; but maybe we need to understand that there is no magic cure in education.

I used to take slideswhenever I went on vacation, for example, and used some to great effect in my American history classes. In that mythic era known as the "Good Olde Days" you could use a slide projector to flash a picture on a screen. It was interesting, though, when computers came into use. The old slides filled the screen no matter how the camera had been held originally. A horizontal landscape, 3" x 5", became a 3' x 5' picuture on the screen.

A portrait taken vertically became a 5' by 3' shot instead.

Here's an old favorite--which I used whenever we talked about John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt and early efforts to save the environment. Muir pushed for Yosemite Park to be protected and devoted his life to drawing boundaries to save sequoia trees from rapacious lumber companies.

I used to ask students how many thought that was a big tree lying on the ground behind my wife (now ex; a nice lady) and virtually all agreed. Then I pointed out that what they were looking at was actually part of a sequoia limb, 150 feet long, before it broke from a tree and shattered on the forest floor. That got everyone's attention.

Unfortunately, when we switched to computers, if you took a picture in portrait mode and flashed it on the screen it was fitted to a computer monitor, shrinking it in size and leaving large blank spaces to left and right. So: if I wanted to show this picture from a cross country bicycle ride I took in 2007, with the old slide projector method it looked like this:

And if I used the computer to flash the picture on a screen it looked like this:

What I discovered, I think was this: you had to interest students in real learning. Old-fashioned notes on a blackboard, with chalk = regular flathead screwdriver. New-style notes in Power Point, with computer = electric screwdriver.

The real question remained, whether you worked with old tools or new: What did you and your students plan to build?

If I was still teaching--and the subject of the environment came up in class today--I might show students this picture from the top of Tioga Pass in Yosemite National Park, taken near the end of another cross country bicycle trip this summer. I think, slide projector or computer, it might gain a little adolescent attention and lead a class into a stirring discussion along the way.

"Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys," he grumbled, "which distract our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end...We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate."

That probably sums up every status update I've posted for the last six months.

I remember when my old school district started bringing computers into classrooms and setting up computer labs and hearing that technology was going to revolutionize education. I remember learning how to use Power Point and how to upload pictures from the Internet for use in lesson plans.

It was going to be great!

Now, instead of the tired old way, writing "AMERICAN CIVIL WAR (1861 to 1865)" on the blackboard with a piece of chalk, we could put it into Power Point. Then the letters would come flying out of a corner of the computer screen and spell out:

"AMERICAN CIVIL WAR (1861 to 1865)"

You could even add sound effects, like cannon crashing and horses whinnying. Unfortunately, students still had to memorize the same fact.

Of course, computers opened up a vast ocean of knowledge to students. Some dived in; and others merely dipped their toes. Others, still, walked the beach checking out the hot young guys and the tanned girls in their bikinis.

In fact, if you took a class to the computer lab and put everyone to work some students buckled down, and got excited about what they could find. Others surfed the web when you weren't looking or played electronic Solitaire. You could find interesting primary sources on the web; or you could go to Wikipedia, do a bit of quick cutting and pasting, and turn in the mishmash as "original" work and hope your teacher went away. You could even find sites pedaling pre-written term papers on all kinds of subjects for the right price. Or you could go to YouTube and find helpful tips on how to cheat on tests.

One suggestion: A) tear off old label from a Desani water bottle; B) scan label on computer; C) write tiny cheat sheet notes on back of new label: D) glue fake label back on bottle; E) carry bottle to next test. Drink as needed and refresh.

Improved means to an unimproved end.

I don't mean to sound like a Luddite here; I know computers can help good teachers in the classroom; but maybe we need to understand that there is no magic cure in education.

I used to take slideswhenever I went on vacation, for example, and used some to great effect in my American history classes. In that mythic era known as the "Good Olde Days" you could use a slide projector to flash a picture on a screen. It was interesting, though, when computers came into use. The old slides filled the screen no matter how the camera had been held originally. A horizontal landscape, 3" x 5", became a 3' x 5' picuture on the screen.

A portrait taken vertically became a 5' by 3' shot instead.

Here's an old favorite--which I used whenever we talked about John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt and early efforts to save the environment. Muir pushed for Yosemite Park to be protected and devoted his life to drawing boundaries to save sequoia trees from rapacious lumber companies.

I used to ask students how many thought that was a big tree lying on the ground behind my wife (now ex; a nice lady) and virtually all agreed. Then I pointed out that what they were looking at was actually part of a sequoia limb, 150 feet long, before it broke from a tree and shattered on the forest floor. That got everyone's attention.

Unfortunately, when we switched to computers, if you took a picture in portrait mode and flashed it on the screen it was fitted to a computer monitor, shrinking it in size and leaving large blank spaces to left and right. So: if I wanted to show this picture from a cross country bicycle ride I took in 2007, with the old slide projector method it looked like this:

And if I used the computer to flash the picture on a screen it looked like this:

What I discovered, I think was this: you had to interest students in real learning. Old-fashioned notes on a blackboard, with chalk = regular flathead screwdriver. New-style notes in Power Point, with computer = electric screwdriver.

The real question remained, whether you worked with old tools or new: What did you and your students plan to build?

If I was still teaching--and the subject of the environment came up in class today--I might show students this picture from the top of Tioga Pass in Yosemite National Park, taken near the end of another cross country bicycle trip this summer. I think, slide projector or computer, it might gain a little adolescent attention and lead a class into a stirring discussion along the way.

Thursday, December 22, 2011

War on Christmas: The Muslim Under the Bed

Anyone who knows me knows I'm a liberal. So you figure I'm not worried about what Fox News likes to call the "War on Christmas."

I don't believe President Obama is a Muslim, either, and even if he was I wouldn't care. I know plenty of good Muslims--good Jews--good Mormons--and good Evangelicals, too. I'm also old enough to remember a time when people said we couldn't elect John Kennedy president, because he'd be loyal to the pope and not the U. S. Constitution.

Religion, of course, has been mentioned frequently in all the recent Republican presidential debates. Rick Perry ran a commercial accusing President Obama of leading a war against religion. Michelle Bachman wants to be president so she can uphold Biblical truths and stop gays from marrying. Newt Gingrich is promising, if elected in 2012, to set up a commission his first day in office "to examine and document threats or impediments to religious freedom in the United States." I'm waiting for Mitt Romney to insist we follow the Biblical admonition to stone adulterers.

I just want to see Newt's face.

Sometimes, though, I wonder if all this talk isn't distracting us from serious issues. Kind of like saying, "There's a boogie man under the bed," to scare little children.

You may have heard the usual complaints: the Bible has been driven from our schools, Christmas vacation is now referred to as Winter Break, and the imposter in the White House, the guy without the birth certificate, is forcing schools to focus on Islamic teachings. But the lines here are fairly clear and state and federal courts are tasked quite often to make them even clearer.

I was an American history teacher for many years, and near the end of my career taught Ancient World History. So you have to talk about religion to get a grip on human history. The Pilgrims crossed an ocean to practice their beliefs and so did the larger Puritan body that settled in New England ten years later. In fact, before we bewail our modern, godless society we should keep in mind that the Puritans whipped Baptists and executed Quakers for bringing their interpretations of the Bible into the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

And where was Rush Limbaugh when we needed him in 1711? Our Puritan forebearers banned all Christmas celebration!

Three centuries later, what can public schools actually do in the realm of teaching religion? In Ancient World History we were expected to examine five world religions (Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam), not because President Obama said so, but because the Ohio Department of Education gave us a curriculum. In American history we included material about the Quakers, who settled Pennsylvania, the Mormons, who settled Utah, and for fun I did a lesson on the Shakers. For those who might not remember: the Shakers were a millenialist sect, started by Ann Lee, who believed the end of the world was imminent. In order to focus attention on matters of the spirit all Shakers were celibate. Membership peaked at 6,000 in 1860, for obvious reasons, and has been declining ever since.

No insult intended to the nine Shakers still remaining.

You can discuss religion in public schools. (I did go out on a limb, when we mentioned the Aztec practice of human sacrifice; I said that that was wrong.) I once organized a debate on religion in my Ancient World classes and asked five kids in every class to volunteer. They would be required to outline their own beliefs and explain their positons on various issues. The only ironclad rule would be: No insulting other students' beliefs. And they would be graded only on how they laid out their beliefs and not on what those beliefs might be. I used to do projects in my classes--a project counted as a test grade--and this debate would be a project. The kids, all volunteers, were incredible. The other students were allowed to ask questions, and I asked a few, but the thirty students (five each in six classes) held center stage for the entire period. They made their classmates think and had to examine their own beliefs.

They even made me think.

In other words, have no fear, freedom of religion is alive and well in America, and if you want to join the Shakers, they'd be happy to have you, I'm certain. And if you're worried about gay marriage, and you're really conservative, don't let it ruin your holiday celebrations. God is going to get those homosexuals in the end and they're going to burn in hell.

I don't believe that, by the way, but that's just my opinion; and so here's what you can't do in public schools. If a student says gays are going to burn in hell, you can't tell him he's wrong. If a gay student in the same class speaks up and says the other student is incorrect, you can't tell him to shut up, either. If I'm a Catholic teacher in the public schools, I can't read to students every morning from the Latin Vulgate Bible, because that version differs in important points from the King James version, preferred by Presbyterians and others. If I a Jewish teacher, I can't tell a Mormon kid his religious book is bogus; and if I'm a Mormon, I can't tell a Muslim kid the Koran is rubbish. If mom and dad are Scientologists, and a student brings up L. Ron Hubbard for discussion, I have to bite my tongue and can't tell that child to be silent. Nor can a teacher say to a child who professes to be an atheist or an agnostic that his or her ideas are wrong.

If you believe the U. S. government is forcing schools to teach Islamic ideas exclusively, you're really worrying about the boogie man under the bed, or, rather the Muslim under the bed. The U. S. government is blocked in all attempts to force religious teachings of any kind on students.

State governments determine curriculum and state governments are similarly blocked from imposing any particular religious views.

With that, let me say to all, conservative and liberal alike: "Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year."

I don't believe President Obama is a Muslim, either, and even if he was I wouldn't care. I know plenty of good Muslims--good Jews--good Mormons--and good Evangelicals, too. I'm also old enough to remember a time when people said we couldn't elect John Kennedy president, because he'd be loyal to the pope and not the U. S. Constitution.

Religion, of course, has been mentioned frequently in all the recent Republican presidential debates. Rick Perry ran a commercial accusing President Obama of leading a war against religion. Michelle Bachman wants to be president so she can uphold Biblical truths and stop gays from marrying. Newt Gingrich is promising, if elected in 2012, to set up a commission his first day in office "to examine and document threats or impediments to religious freedom in the United States." I'm waiting for Mitt Romney to insist we follow the Biblical admonition to stone adulterers.

I just want to see Newt's face.

Sometimes, though, I wonder if all this talk isn't distracting us from serious issues. Kind of like saying, "There's a boogie man under the bed," to scare little children.

You may have heard the usual complaints: the Bible has been driven from our schools, Christmas vacation is now referred to as Winter Break, and the imposter in the White House, the guy without the birth certificate, is forcing schools to focus on Islamic teachings. But the lines here are fairly clear and state and federal courts are tasked quite often to make them even clearer.

I was an American history teacher for many years, and near the end of my career taught Ancient World History. So you have to talk about religion to get a grip on human history. The Pilgrims crossed an ocean to practice their beliefs and so did the larger Puritan body that settled in New England ten years later. In fact, before we bewail our modern, godless society we should keep in mind that the Puritans whipped Baptists and executed Quakers for bringing their interpretations of the Bible into the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

And where was Rush Limbaugh when we needed him in 1711? Our Puritan forebearers banned all Christmas celebration!

Three centuries later, what can public schools actually do in the realm of teaching religion? In Ancient World History we were expected to examine five world religions (Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam), not because President Obama said so, but because the Ohio Department of Education gave us a curriculum. In American history we included material about the Quakers, who settled Pennsylvania, the Mormons, who settled Utah, and for fun I did a lesson on the Shakers. For those who might not remember: the Shakers were a millenialist sect, started by Ann Lee, who believed the end of the world was imminent. In order to focus attention on matters of the spirit all Shakers were celibate. Membership peaked at 6,000 in 1860, for obvious reasons, and has been declining ever since.

No insult intended to the nine Shakers still remaining.

You can discuss religion in public schools. (I did go out on a limb, when we mentioned the Aztec practice of human sacrifice; I said that that was wrong.) I once organized a debate on religion in my Ancient World classes and asked five kids in every class to volunteer. They would be required to outline their own beliefs and explain their positons on various issues. The only ironclad rule would be: No insulting other students' beliefs. And they would be graded only on how they laid out their beliefs and not on what those beliefs might be. I used to do projects in my classes--a project counted as a test grade--and this debate would be a project. The kids, all volunteers, were incredible. The other students were allowed to ask questions, and I asked a few, but the thirty students (five each in six classes) held center stage for the entire period. They made their classmates think and had to examine their own beliefs.

They even made me think.

In other words, have no fear, freedom of religion is alive and well in America, and if you want to join the Shakers, they'd be happy to have you, I'm certain. And if you're worried about gay marriage, and you're really conservative, don't let it ruin your holiday celebrations. God is going to get those homosexuals in the end and they're going to burn in hell.

|

| Chirstmas is alive and well. |

If you believe the U. S. government is forcing schools to teach Islamic ideas exclusively, you're really worrying about the boogie man under the bed, or, rather the Muslim under the bed. The U. S. government is blocked in all attempts to force religious teachings of any kind on students.

State governments determine curriculum and state governments are similarly blocked from imposing any particular religious views.

With that, let me say to all, conservative and liberal alike: "Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year."

Monday, December 12, 2011

Rock, Voucher, Scissors: Saving Carl Won't Be that Easy

RECENTLY, I HAD A CHANCE TO TALK to a former student, now teaching first grade in a Southeast Ohio school district. She works diligently at her craft and tries in every way she can to help her young charges.

She’s a little testy when she hears another story about “what’s wrong with America’s teachers.” She knows there are bad teachers. She’s not blind. I taught 33 years, myself. I’m not blind to that reality either.

Still, when you hear Governor John Kasich in Ohio or some leading school reformer talking about how more vouchers and more charter schools will cure all problems in education, well, if you’re a teacher, it starts to grate on your nerves.

Here’s a situation my former student currently faces. In her class she has a boy who doesn’t talk. To be exact: he doesn’t talk much to peers, to adults normally not at all. One of his classmates comes up to her (we’ll call her Ms. Smith) occasionally, and says, “Miss Smith, Carl talks to me.”

Otherwise, the six-year-old is a selective mute. He could talk but chooses not to.

At first, Smith and various therapists assumed Carl had an anxiety disorder. If they could help him relax he might improve. Smith provides a nurturing classroom environment and has been breaking through on rare occasions. There’s a long road ahead and the journey is painful and slow.

A few days ago the boy’s great uncle stopped by to speak to her. “I don’t want to talk behind my niece’s back,” he began, “but I need to explain the situation at home. Carl was born with cocaine in his system and his mom has been an addict most of her life.”

Miss Smith has been teaching for eight years, in a poor district, and though every suffering family suffers in its own unique way, she’s heard this kind of story before. She listens while the uncle continues: “Mom has had one child taken away by Children’s Services. [Like Carl, his sibling was born with drugs in his system had to suffer withdrawal pains while in the crib.] We’re trying to help her keep Carl, but the drugs have damaged her thinking. She’s like a child and we have to watch her all the time. Until recently, my niece was broke and she and the boy were living out of a cheap motel.”

“It’s been a struggle,” the uncle admitted. At that point, he began crying.

Ms. Smith is a good teacher—the vast majority of the people who staff our classrooms are. So she’s not giving up and does everything in her power to help.

It’s kind of disheartening, though, for her to keep reading about how vouchers and charter schools will solve all the problems in America’s schools.

Ms. Smith is too busy trying to help real kids to make this kind of promise.

But I’m a retired teacher and willing to make a bet. I don’t believe anyone out

there, not even U. S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, can explain how a

school voucher, a single sheet of paper, allowing Carl to change schools, or a

charter school, itself, is going to shield this poor boy from more of the same

kind of cruel vicissitudes he has so far met with in a very short life.

A “parent voucher” might help, instead. Carl often begs his uncle to adopt him, but his uncle is poor, and too old to start over raising a six-year-old. Even a “housing voucher” might help.

A school voucher?

If you can show me how a chance to change schools is going to solve this child’s problems, I’ll eat a school voucher and won’t even bother to wash it down with beer.

P. S. This sort of situation is far from rare and in the end there’s not a syllable of humor in it. If you’re Ms. Smith or any other dedicated teacher you want to hear experts in education outline a plan to really help these kids.

According to the New York Times, nearly 1 in 10 babies born in Scioto County, in Southern Ohio, last year tested positive for illegal drugs in their blood.

In 2008-2009, the U. S. Department of Education estimated that there were 954,917 homeless children in this country.

Meanwhile, Mayor Bloomberg, the billionaire school reformer, says the real problem in education is that teachers are culled from the bottom 20% of college graduates, and not from the best schools. Bloomberg, a Harvard graduate himself, and therefore an expert in helping poor children, is thinking about buying a modest home in Southampton, a 22,000 square foot place nestled on 35 acres.

Maybe the mayor could find room in his “cottage” for a couple of homeless kids.

She’s a little testy when she hears another story about “what’s wrong with America’s teachers.” She knows there are bad teachers. She’s not blind. I taught 33 years, myself. I’m not blind to that reality either.

Still, when you hear Governor John Kasich in Ohio or some leading school reformer talking about how more vouchers and more charter schools will cure all problems in education, well, if you’re a teacher, it starts to grate on your nerves.

Here’s a situation my former student currently faces. In her class she has a boy who doesn’t talk. To be exact: he doesn’t talk much to peers, to adults normally not at all. One of his classmates comes up to her (we’ll call her Ms. Smith) occasionally, and says, “Miss Smith, Carl talks to me.”

Otherwise, the six-year-old is a selective mute. He could talk but chooses not to.

At first, Smith and various therapists assumed Carl had an anxiety disorder. If they could help him relax he might improve. Smith provides a nurturing classroom environment and has been breaking through on rare occasions. There’s a long road ahead and the journey is painful and slow.

A few days ago the boy’s great uncle stopped by to speak to her. “I don’t want to talk behind my niece’s back,” he began, “but I need to explain the situation at home. Carl was born with cocaine in his system and his mom has been an addict most of her life.”

Miss Smith has been teaching for eight years, in a poor district, and though every suffering family suffers in its own unique way, she’s heard this kind of story before. She listens while the uncle continues: “Mom has had one child taken away by Children’s Services. [Like Carl, his sibling was born with drugs in his system had to suffer withdrawal pains while in the crib.] We’re trying to help her keep Carl, but the drugs have damaged her thinking. She’s like a child and we have to watch her all the time. Until recently, my niece was broke and she and the boy were living out of a cheap motel.”

“It’s been a struggle,” the uncle admitted. At that point, he began crying.

Ms. Smith is a good teacher—the vast majority of the people who staff our classrooms are. So she’s not giving up and does everything in her power to help.

It’s kind of disheartening, though, for her to keep reading about how vouchers and charter schools will solve all the problems in America’s schools.

|

| I'm ready to make the bet. |

A “parent voucher” might help, instead. Carl often begs his uncle to adopt him, but his uncle is poor, and too old to start over raising a six-year-old. Even a “housing voucher” might help.

A school voucher?

If you can show me how a chance to change schools is going to solve this child’s problems, I’ll eat a school voucher and won’t even bother to wash it down with beer.

P. S. This sort of situation is far from rare and in the end there’s not a syllable of humor in it. If you’re Ms. Smith or any other dedicated teacher you want to hear experts in education outline a plan to really help these kids.

According to the New York Times, nearly 1 in 10 babies born in Scioto County, in Southern Ohio, last year tested positive for illegal drugs in their blood.

In 2008-2009, the U. S. Department of Education estimated that there were 954,917 homeless children in this country.

Meanwhile, Mayor Bloomberg, the billionaire school reformer, says the real problem in education is that teachers are culled from the bottom 20% of college graduates, and not from the best schools. Bloomberg, a Harvard graduate himself, and therefore an expert in helping poor children, is thinking about buying a modest home in Southampton, a 22,000 square foot place nestled on 35 acres.

Maybe the mayor could find room in his “cottage” for a couple of homeless kids.

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

Why Teaching Matters--Part 4 (Books)

JENNY BALL, IF YOU EVER READ this post, I’m sorry. I’m sorry, when I had you in eighth grade, that I drilled a hole through your history book.

You have to admit, though—that textbook was boring.

Despite the occasional mishap with drills, I was a typical teacher. I worked hard, but so did most of my peers. Today we hear constantly about standardized testing, the importance of teaching the basics, and all kinds of complicated new tools to measure what teachers do.

Often, in education, it’s impossible to “measure” what matters. Loveland Middle School, where I worked, had a phenomenal band director, Bruce Maegly, and a choir/play director, Shawn Miller, who was excellent. You’d hear Mr. Maegly’s jazz band perform and swear they were high school kids. Mr. Miller’s students were unbelievable in the plays he staged with their help. We had great coaches, too—Mike Rich, who could lead young men and women to success in pretty much any sport, except NASCAR—and Chuck Battle, who set the bar high when it came to character.

Our art teachers, Bethany Federman and Diane Sullivan, were excellent too.

For thirty years, I taught American history and later did three years of Ancient World History. It was part of the grade in my class to read four books if a student wanted an “A” or a “B” for the year, two for a “C,” one if they wanted to pass with a “D.”

I didn’t assign books though. I don’t think there should be “standardization” where literature is involved.

I wanted students to read works they actually liked. So: if Jason Garnerett wanted to read Lonesome Dove (which he did in two weeks, all 961 pages of it) I didn’t want to stand in his way.

Over the years students in my classes read more than 10,000 books. And I wonder—if we’re going to go to standardized testing — with merit pay based on test scores — how this would all be measured. Take the Holocaust memoir, Night, as one example. It’s short, 116 pages, and sad, and you can’t ask questions on a statewide test about it because not all students would have been exposed to reading it. I only know that hundreds of students in my classes read it and that many were moved to tears.

(I don’t know: Do we measure tears with a bucket?)

Or consider Go Ask Alice, the tale of a teenage girl who fell victim to the allure of drugs. I received this Facebook message from Christina Vogelsang recently, two decades after the young lady passed through my classes:

I love to read, and you got me turned on to a great book called ‘Go Ask Alice’. I believe that book is what kept me from getting into drugs. Loveland has lost several due to drugs, and that book scared the hell out of me! Thank you and Good Job! – You spoke of the book and I remember you had several back behind your desk I do believe?? One thing you did say is that there is no bigger waste of time reading a book you are not interested in. You could not have been more correct! Hahaha! You brought critical thinking to the class room...”

Christina also noted, “Your temper was quite entertaining as well...but then again I wouldn’t want to put up with 30 seventh graders!”

I’ll let that line pass.

(I’m sure none of my other students ever saw me mad.)

So: how do we measure what matters? If M. K. Fisher, a serious-minded young lady reads the Civil War novel, Cold Mountain, does that still count as learning? Most experts believe students exposed to great writing learn how to write effectively. And Cold Mountain grips a reader from the first scene and never loosens that grip.

In the first chapter, Inman, a Confederate soldier, lies in a hospital, badly wounded. Doctors do not expect him to survive a wound to the neck, but he does. Occasionally, he wipes the wound with a rag and dips it in a basin near his bed, “until the water...was the color of the comb of a turkey-cock.”

Does it help a star student like Ms. Fisher, to read this work, to see lines like this, where author describes a character so: “He was a sculpture carved in the medium of lard.”

Gone With the Wind was a hit, too, mostly with girls, but I always cautioned readers to beware of latent racism in a finely-crafted story. At one point, Margaret Mitchell insists Master O’Hara was a good master, who only whipped one slave all his life, for failing to rub down his favorite horse after a hard ride.

Wait. What?

The horse rated higher than the man?

There’s learning there, too; and we used to discuss that. Now tell me: How do we measure it on a standardized test?

John Crawford tells a story “not of the insanity of war, but the insanity of men” in The Last True Story I’ll Ever Tell, about the War in Iraq. As an infantryman Crawford looks with envy upon the comforts he sees on an Air Force base. “My company, on the other hand, slept where we shit and shit next to where we ate.” That’s a sentiment Sam Watkins, in Co Aytch, a Civil War memoir popular with boys, could have understood.

(Obviously, I needed to require a note of parental permission before students could read some of these books.)

What else did my seventh and eighth graders read? Many enjoyed the classic Puddn'head Wilson by Mark Twain. Others loved Black Hawk Down by Mark Bowden. They read Born on the Fourth of July, by Ron Kovacs, a soldier paralyzed from the waist down when hit by enemy fire in Vietnam, and a few tackled Native Son by Richard Wright, too. Johnny Got His Gun, the anti-war novel, was surprisingly popular.

Sadly, in my opinion, A Farewell to Arms was not.

To Kill a Mockingbird was — and it would be hard for any teen to read that work and not come away burning with a desire to end injustice.

(I’m sure none of my other students ever saw me mad.)

So: how do we measure what matters? If M. K. Fisher, a serious-minded young lady reads the Civil War novel, Cold Mountain, does that still count as learning? Most experts believe students exposed to great writing learn how to write effectively. And Cold Mountain grips a reader from the first scene and never loosens that grip.

In the first chapter, Inman, a Confederate soldier, lies in a hospital, badly wounded. Doctors do not expect him to survive a wound to the neck, but he does. Occasionally, he wipes the wound with a rag and dips it in a basin near his bed, “until the water...was the color of the comb of a turkey-cock.”

But mainly the wound had wanted to clean itself. Before it started scabbing, it spit out a number of things: a collar button and a piece of wool collar from the shirt he had been wearing when he was hit, a shard of soft grey metal as big as a quarter dollar piece, and, unaccountably, something that closely resembled a peach pit. That last he set on his nightstand and studied for some days. He could never settle his mind on whether it was a part of him or not.

Does it help a star student like Ms. Fisher, to read this work, to see lines like this, where author describes a character so: “He was a sculpture carved in the medium of lard.”

Gone With the Wind was a hit, too, mostly with girls, but I always cautioned readers to beware of latent racism in a finely-crafted story. At one point, Margaret Mitchell insists Master O’Hara was a good master, who only whipped one slave all his life, for failing to rub down his favorite horse after a hard ride.

Wait. What?

The horse rated higher than the man?

There’s learning there, too; and we used to discuss that. Now tell me: How do we measure it on a standardized test?

John Crawford tells a story “not of the insanity of war, but the insanity of men” in The Last True Story I’ll Ever Tell, about the War in Iraq. As an infantryman Crawford looks with envy upon the comforts he sees on an Air Force base. “My company, on the other hand, slept where we shit and shit next to where we ate.” That’s a sentiment Sam Watkins, in Co Aytch, a Civil War memoir popular with boys, could have understood.

(Obviously, I needed to require a note of parental permission before students could read some of these books.)

What else did my seventh and eighth graders read? Many enjoyed the classic Puddn'head Wilson by Mark Twain. Others loved Black Hawk Down by Mark Bowden. They read Born on the Fourth of July, by Ron Kovacs, a soldier paralyzed from the waist down when hit by enemy fire in Vietnam, and a few tackled Native Son by Richard Wright, too. Johnny Got His Gun, the anti-war novel, was surprisingly popular.

Sadly, in my opinion, A Farewell to Arms was not.

To Kill a Mockingbird was — and it would be hard for any teen to read that work and not come away burning with a desire to end injustice.

I LOVED TEACHING AND LOVED BOOKS and felt convincing students to read more was like getting people to go to the gym to get into great intellectual shape. So, I had weak students, who needed help, who read Sounder, and one who finished a biography of General Custer in the eighth grade and told me it was the first book he had ever read. At least one young lady, Martha Hoctor, liked Walden and one young man finished The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, all 1,141 pages, for my eighth grade history class.

I gave kids as much latitude as possible. Several read Empire Falls, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about a failing New England town. (Typical line: “It was the particular curse of the Whiting men that their wives remained loyal to them out of spite.”) Maus and Maus II, comic book-tellings of the story of the Nazis, as cats, and the Jews, as mice, were immensely popular and again students were exposed to Pulitzer Prize literature.

|

| The Jews are mice and the Nazis are cats in this telling of the Holocaust story. |

From where I stood, at the front of a classroom, I thought it was obvious that reading more was the surest and broadest path to intellectual growth. So, yes, I think teaching matters and I’m proud of what I tried to do.

TOO BAD MOST OF OUR EDUCATION EXPERTS never taught and can’t understand this basic truth.

P.S. I’m still reading in retirement.

If I was still working with kids I might recommend the great new novel about the war in Iraq: The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers.

I think seventh and eighth graders might also enjoy The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. A few might also be up for the challenge of reading Becoming Madame Mao by Anchee Min. The latter might help them understand the dangers of unchecked government power.

With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa by E. B. Sledge might be the single best story about combat during World War II that I have ever read.

Finally, I know I could challenge some of my students to read Matterhorn by Karl Marlantes. It’s a novel about the Vietnam War by an author who served in combat and one of the most powerful works of fiction I’ve ever read. In a typical scene, American forces are defending a hill from enemy attack. When they come under heavy fire, Marlantes describes the scene this way: “The wounded [American soldiers] lay along the east side of Matterhorn. The mortar shells walked with fiery feet among them, occasionally stumbling on one, leaving a meat-red footprint.”

Such is the powerful imagery that fills the book; and in a world prior to standardized testing, I’d have loved to recommend Marlantes’ story to all my classes and know the book would have been popular.

It just wouldn’t have been standardized learning.

Sunday, December 4, 2011

Why Teaching Matters--Part 3

You know the Big Buzzword in American education today is "standardized learning." So I'm going to let you in on a secret: Most of what matters in teaching can't really be measured. (It's like trying to say, "We need standardized parenting.")

In my history classes, for example, we used to do all kinds of projects--and since students could choose the kinds they did, they almost always played to their talents and strengths. I used to be a terrible student, myself, when I was a teen. A bit of a bad attitude. Even got an "F" in eighth grade art.

So, thirty years later, my students scoffed at my drawing abilities (see example, left).

Luckily, I had kids with all kinds of gifts. So, if they wanted to do debates, like Chris Dorgan and Chelsea Williams, they did debate projects. If they wanted to do creative writing, they could do creative writing, like D. J. Kimble and Andrea Dearden. My last year in teaching, Christian Barnett loved building models. I encouraged him to do models for projects and he did wonderful work. Zach Fein and Mitul Desai, a few years earlier, did a fantastic scale model of Auschwitz. I gave them an "A+" without really having to think about it.

Zach went on to become an architect.

In other words: you never know what seeds you plant when you plant knowledge and you can't be sure how they'll grow.

Recently, I was looking over a few examples of art projects I happened to keep. I wish I'd kept a thousand more; but when you turn students loose and let them use their talents, that's where knowledge truly blossoms, in individual ways.

Think about "standardized education" in terms of 9/11, for example.

If you were following a set curriculum in 2001, technically, you would have been in violation for stopping to examine the story, since it would have happened after "standards" were already set in stone. In my class, at that time, however, I was able to let students do projects on a topic that interested them. Two young ladies, Courtney Allen and Tara Main, turned in a Pop-Up Book on September 11.

Unfortunately, once No Child Left Behind was fully implemented, here in Ohio we were stuck following a strict new curriculum.

So: if we're teaching Ancient World History, what's the one fact about Islam you'd think I should teach? Because that's all there's going to be on the standardized test every year.

One fact about Islam.

When Chase Giles does an Alphabet Book on Islam, then, are 25 pages wasted? Does depth of understanding count for nothing? That doesn't make sense.

I think it mattered--to focus on empathy--even if that can't be measured on a standardized test.

I think it mattered that Ian and so many others had a chance to exercise their gifts in ways they chose themselves.

Teaching always mattered.

|

| My kind of art. |

So, thirty years later, my students scoffed at my drawing abilities (see example, left).

Luckily, I had kids with all kinds of gifts. So, if they wanted to do debates, like Chris Dorgan and Chelsea Williams, they did debate projects. If they wanted to do creative writing, they could do creative writing, like D. J. Kimble and Andrea Dearden. My last year in teaching, Christian Barnett loved building models. I encouraged him to do models for projects and he did wonderful work. Zach Fein and Mitul Desai, a few years earlier, did a fantastic scale model of Auschwitz. I gave them an "A+" without really having to think about it.

Zach went on to become an architect.

In other words: you never know what seeds you plant when you plant knowledge and you can't be sure how they'll grow.

Recently, I was looking over a few examples of art projects I happened to keep. I wish I'd kept a thousand more; but when you turn students loose and let them use their talents, that's where knowledge truly blossoms, in individual ways.

Think about "standardized education" in terms of 9/11, for example.

If you were following a set curriculum in 2001, technically, you would have been in violation for stopping to examine the story, since it would have happened after "standards" were already set in stone. In my class, at that time, however, I was able to let students do projects on a topic that interested them. Two young ladies, Courtney Allen and Tara Main, turned in a Pop-Up Book on September 11.

|

| Driving to work on a beautiful September day. (Allen and Main.) |

|

| At work in an office--before the attack. (Allen and Main.) |

So: if we're teaching Ancient World History, what's the one fact about Islam you'd think I should teach? Because that's all there's going to be on the standardized test every year.

One fact about Islam.

When Chase Giles does an Alphabet Book on Islam, then, are 25 pages wasted? Does depth of understanding count for nothing? That doesn't make sense.

|

| (Art by Chase Giles.) |

|

| (Art by Chase Giles.) |

The first year I ever taught Ancient World History, I decided to have my students read parts of Homer's Iliad; and again they responded. In that case, one project possibility was to join the cast and crew of a comic play, called "Jessica of Troy," the story of Hector, Paris, Helen, Achilles and Jessica Simpson. We even added a Greek chorus for students who liked to sing. Alex Neal, Suzie Culbertson and Anna Eltringham all excelled, as did dozens more.

Amanda Shelton was more artistically inclined. So she did a series of sixteen water colors on the same topic--well, not Jessica, of course.

For most of my career I taught American history and we used to do a lesson on Father Bartolomew Las Casas, a Spanish priest, who tried to save Native Americans from abuse. In a reading I prepared for students, it mentioned soldiers throwing babies into a river and calling out, "boil there you offspring of the devil." So we talked at length about "labels" people use to describe those they don't like (i. e. fag, jock, nerd, kike, gook, nigger), and about how this leads to "dehumanization." Finally, we talked about the antidote. We talked about empathy.

Amanda Shelton was more artistically inclined. So she did a series of sixteen water colors on the same topic--well, not Jessica, of course.

|

| Paris leaps from the ranks of the Trojans to battle Menelaus. (Amanda Shelton.) |

|

| Andromache tries to convince Hector to avoid his fight with Achilles. (Amanda Shelton.) |

|

| Achilles drives his spear into Hector's neck. (Amanda Shelton.) |

Ian Wagers, took the lesson to heart and turned it into a wonderful comic book:

|

| Father Antonio was one of the first priests to warn settlers that what they were doing was wrong. (Ian Wagers.) |

|

| At first, Las Casas did not care about the natives. He changes his mind, freed his own slaves and became a priest. The book he wrote was titled: A Brief History of the Indies. (Ian Wagers.) |

I think it mattered that Ian and so many others had a chance to exercise their gifts in ways they chose themselves.

Teaching always mattered.

Friday, December 2, 2011

Why Teaching Matters--Part 2

|

| Where do we lead students? We may never know. Drawing by Matt Mouser, former student. |

That’s right. I spent my life in the company of hormonal teens.

So I learned to use some “unconventional” methods to keep students interested. Not that my lectures weren’t scintillating, I don’t mean.

I hated wasting class time for any reason whatsoever; but if I thought I could keep kids engaged I was ready to try anything. One day, Susan -----, a lively, funny young lady, made the mistake of telling me class was boring. She was an exceptional student. If she said class was boring it probably was.

I said we needed to liven up.

Susan foolishly agreed.

So, I picked up her books and threw them out a window onto the school lawn.

That woke Susan and everyone else up, even me.

Another time, the homework paper of a top student floated off her desk and landed in the center of the room. (We had desks in a horseshoe arrangement.) I walked over to pick it up and had an inspiration. Saying, “Here, let me get that,” I placed one foot on the paper, grabbed to pick it up and ripped it in two. I stood there staring at half a paper in disbelief.

“That was my HOMEWORK,” the owner of the dismembered assignment exclaimed. “What am I going to do now?”

“I’ll give you an automatic A,” I replied, and the class roared and that’s what we did.

IF I EVER WONDERED WHETHER these kinds of tactics were effective, the first great letter I received from a former student resolved the question. It came in the mail one day, after I had been teaching seven or eight years.

Joey was bright and impossible not to like but his grades in my class and every other were terrible. He missed homework diligently. He missed five assignments. We talked. He missed seven more. We talked. He ran his string of missing assignments to twenty—thirty—headed towards forty, like Joe DiMaggio in reverse.

Around that time, I hit upon the idea of fishing in my pocket occasionally and saying to my class in a game show announcer’s voice: “You can win all the money (jingling sound) in this pocket if you answer the next question.” Sometimes I would pull out the coins and show them for effect. “This entire thirteen cents, one dime and three pennies, can be yours if you tell me who wrote the Declaration of Independence.”

Every so often I offered “big money.” In morning classes one day I gave a dime to the first student able to name the first astronaut to walk on the moon. In every class someone could. So it took a few dimes to generate a little enthusiasm. I started offering fifty cents—a huge prize—if anyone could name the three astronauts who took part in the first moon landing mission. The letter I received explains what happened next and shows how much teaching can matter.

If you will, try and think back 5 or 6 years…In your history class I received the honor of having the most consecutive zeroes in your teaching career, I believe it was 32 or 37. In class I also received 50¢ for naming the two other astronauts that were with Neil Armstrong. And I will never forget your ability to throw erasers at pupils who were talking while you were conducting class, namely myself. I was one of the worst students in the junior high that year. Can you remember.

The reason I am writing you is... to say thanks. You made me realize that if I didn’t straighten my life out I would end up being a bum.

It took me 2 years after having you for history to realize you were right. After my freshman year at Loveland Hurst, which was a joke, I moved to Grant County, Kentucky. I figured I would start out with a clean slate and settle down. I started doing my homework, a first, right? Believe it or not I was well respected there. I found enjoyment in excelling in my school work. I almost majored in mathematics in high school. I received an award in my poetry class. Get this I Joey ----- was the only student to keep an “A” average in poetry class. I also got a couple of awards in Band. I have graduated high school this year and I am now attending the University of Kentucky. You will never believe what I plan to study, I am a pre-medicine student. You didn’t faint did you? I am doing fine in college and I want to repeat a humble thank you. It seemed that you knew I had the potential and tried to bring it out of me but I would not allow you. Thank you.

Your friend forever,

Joey -----

You see: teaching always matters.

P. S.: If there’s any teacher out there who wants to copy my “big cash prize idea,” I say go ahead.

I would warn you, however. NEVER offer $5 to anyone who can answer some question you consider hopelessly abstruse. When they do you will end up poorer and wiser.

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Why Teaching Matters--Part 1

I've been retired from teaching now for three years and don't miss the grind. I loved life in the classroom, but if you're doing the job right, the demands are unending. So for a few blog posts, I'm going to try to explain why teaching matters.

Food was in short supply and soldiers were soon reduced to eating nothing but “fire cake,” a mix of flour and water cooked over a fire.

Of course, young teachers enter the classroom believing they can save every child. And today politicians who couldn’t save a kitten stuck in a bush insist this miracle can be achieved on a national scale.

(See: No Child Left Behind.)

If you plan to survive in teaching, however, you must divest yourself of this delusion or prepare for prolonged bouts of depression. You must try to save every child. That you must do. You must assume there is potential in every head and do everything in your power to tap it. But you must be ready for failure.

You are a teacher.

Not a magician.

It's not just academics, either. You talk to the 14-year old girl, who has been lying about her age and seeing a 36-year-old man. You listen to the boy, who is being bullied, and has been spat upon, and you go look up the bully, yourself. You talk to the mom who doesn't know how to control her teenage daughter; and you tell her not to nag and berate. You tell her to remember the words of Anatole France: “The more you say, the less people remember.”

Good advice when dealing with teens.

For most of my career I taught American history. Early on, I stumbled across a type of activity that seventh and eighth graders loved, and one at which they excelled. We were doing a long reading on the famous winter at Valley Forge (which I wrote myself). At one point the reading included this section:

Food was in short supply and soldiers were soon reduced to eating nothing but “fire cake,” a mix of flour and water cooked over a fire.

Dr. Waldo [an officer in Washington's army who kept a journal] jokingly described the diet. “What have you got for Dinner Boys?” he asked the men one afternoon: “Nothing but Fire Cake and Water, Sir.” Again that evening he asked: “Gentlemen, the Supper is ready. What is your Supper, Lads?” Once more they shouted, “Fire Cake and Water, Sir.”

We spent part of class discussing some of the tough vocabulary and then students were told to finish the reading that night.

On the drive home that afternoon, I began thinking over more creative ways to use the material. Instead of giving a quiz, I decided to do a short skit to start class the next day.

Now, when students filed in and took their seats, I explained that we would be having a “fire” in the center of the room and “soldiers” would sit around it warming themselves over the flames. We needed volunteers to discuss camp life. Hands shot up all over the room.

Good start. Students liked the idea.

Good start. Students liked the idea.

The first group to act out the scene started slowly and it looked like the idea might fizzle. Then one of the boys took off a shoe and threw it in the “fire,” saying, “At least we’ll have something to eat besides fire cake.” His “comrades” nodded and rubbed their hands and looked dejected. A chronic complainer in class starred--as a chronic complainer in Washington’s army.

In another bell, two volunteers set their shoes aside before the skit and plunked down beside the fire in stocking feet. After a few minutes, one keeled over “dead.” The other soldiers sniffed loudly, from cold or sorrow we knew not which. Then one of them tugged off the dead man’s socks and placed them on his frostbitten hands like mittens.

A second exclaimed, “Dibs on his underwear!”

This brought moans and laughter from the audience and I knew we had stumbled onto something big.

Once it became clear that classes enjoyed doing skits we began experimenting. But it was the suggestion of a young lady in one of my morning classes that sent us digging deeper into this rich lode. I was still a young teacher at the time and Lisa was one of Loveland’s rare minority students. Her grades were fair at best, and the girl could be a pain if she disagreed with your teaching methods.

Still, Ms. ----- knew how to think.

One day she approached my desk. We had just started a unit on the South in the years before the Civil War. She bent close and whispered: “I think we should do a skit about slavery.”

Normally, I might have steered away from the topic, lest we seem insensitive. Lisa’s enthusiasm, however, altered my thinking. The two of us whispered back and forth before settling on a “panel discussion” involving slaves and slave owners. Lisa volunteered at once to play a slave. When we explained her idea there were plenty of volunteers. John, who liked to argue with Lisa anyway, agreed to play her master. We picked a second “master” and explained that none of her slaves would be present for the skit. Then we selected two more “slaves.” They would be from different plantations and their owners would also be absent.

This gave variety of perspective.

In years to come thousands of students took part in all kinds of skits and it was often subtle touches that made their performances great. In Lisa’s case she wore a blue bandanna round her head and adopted a field hand’s manner of speech. She also ran the kind of chain you use to secure a dog in your yard round her wrists and through her belt loops and jingled it whenever John claimed to be a “good master.” John picked up on every cue and threatened “trouble” when they returned to their plantation. Lisa refused to be cowed, saying if he beat her “like always” she was not afraid.

At some point, John insisted slaves sang in the fields because they were happy. Lisa objected and said music lightened the load of sorrow bearing down upon their souls. She sang a few verses from a Negro spiritual and explained their hidden meaning to make the point.

This panel discussion--the brain-child of one creative young lady--was the first skit we ever did intended to last the entire period.

Lisa and four classmates held center stage for forty-five minutes and all five earned A’s.

Lisa and four classmates held center stage for forty-five minutes and all five earned A’s.

Of course, young teachers enter the classroom believing they can save every child. And today politicians who couldn’t save a kitten stuck in a bush insist this miracle can be achieved on a national scale.

(See: No Child Left Behind.)

If you plan to survive in teaching, however, you must divest yourself of this delusion or prepare for prolonged bouts of depression. You must try to save every child. That you must do. You must assume there is potential in every head and do everything in your power to tap it. But you must be ready for failure.

You are a teacher.

Not a magician.

When I first met Conan, near the end of my career, he had already been held back twice. In other words, he had a reputation for failure. A tall, thin kid, he favored Gothic clothing, and on first glance appeared to be the kind of character who might cause discipline problems. As it turned out, he rarely did homework and his test scores were low. But he was quick-witted and funny and had a maturity (partly based on age) that gave him the edge in discussion. I sensed he’d be a natural in skits and encouraged him to join a group preparing a presentation on Pilgrims and Indians.

The day of the skit when everyone else was ready, Conan insisted he needed more time. My heart sank. I thought he meant he hadn’t studied. No, he said, he needed time to dress. I sent him to the restroom. Five minutes passed. We sent a scout to find him. The scout returned.

No Conan.

I was starting to wonder if he might have skipped out the back when an old lady in a full-length black dress and white lace collar, gray hair pulled back in a bun, entered the room. Granny sported blue-tinted hippie glasses.

For the next forty minutes Granny was as good as anyone I ever saw in a skit. He (she?) knew why the Pilgrims went to Holland in 1609, before they came to America, and why they left, what weather was like when they arrived on these shores, and cackled as he explained. Sometimes he stumbled over answers, but only in character, as if memory was fading with age. He said he was shocked when the natives mooned the settlement. (That's a little know story involving the Pilgrims, not something we usually talk about on Thanksgiving Day.)

And he said it like he meant it.

Once he hiked his dress to show a little Pilgrim ankle and called out in my direction: “Hey, baby, give me a call!” His classmates were enthralled.

And he said it like he meant it.

Once he hiked his dress to show a little Pilgrim ankle and called out in my direction: “Hey, baby, give me a call!” His classmates were enthralled.

When the bell was about to ring we ended a minute early so I could tell everyone what a wonderful job they had done. I singled Conan out for praise. “How many think Conan deserves an ‘A+’?” Every hand went up and we awarded him a perfect score by acclamation.

It wasn't standardized learning, of course--and it didn't mean Conan's personal problems and troubles at home had suddenly evaporated.

Still, for one day, the young man had reason to feel proud.

It wasn't standardized learning, of course--and it didn't mean Conan's personal problems and troubles at home had suddenly evaporated.

Still, for one day, the young man had reason to feel proud.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)